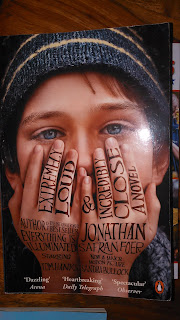

Just occasionally, there comes along a book that blows me away. In this case, I am rather late to the party, but there are good reasons for that, which we will see later. On holiday, I found this book, and thought I would give it a go, and I found an absolute gem of a book.

It was interesting that one of the influences on this book was Kurt Vonnegurt's Slaughterhouse Five, which I had just started reading at the same time. That was odd. Another influence is probably Laurence Stern and Tristram Shandy (another clever book), or possibly James Joyce, but without the incomprehensibility. It is a novel that relies on the book format, and uses that format cleverly and intelligently.

OK, there is a reason why I would probably have avoided this book when it first came out (some ten years ago). The event that triggered off my depression was the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Centre, and I have tended to avoid references and discussion of this, because I have found it triggery. I noted that this book had references to this, but I hadn't realised quite how closely connected it was. However, I found this story therapeutic instead, probably because of the way that it was written.

The story is told from the perspective of a 9 year old Oskar Schell, working through his dads death in the 9/11 attack. He finds a key that he believes will help him find out more about his dad, and he spends a lot of the book looking for the lock that fits the key - which one of some 16Bn locks in New York. When he finds the answer to this puzzle, it doesn't, in fact, bring him closer to his dad, but the search has enabled him to move on. He doesn't find the answers that he wanted, but he does find some resolution. In truth, as I read this and worked through Oskars loss, I also found some answers, some resolution.

There is another story behind this, which is Oskars grandfather in Dresden during the bombing. There is, I think, a parallel between the devastation in Dresden, and the resultant rebuilding of lives beyond this - leading, two generations later to Oskar - and the necessary rebuilding of lives after 9/11. It is a story of rebuilding after destruction. It is a story of finding answers that are not necessarily the answers to the questions we are asking. It is the story of finding meaning in the meaningless.

In Oskars search for meaning, a search that is ultimately fruitless but in which he does find answers, I have found healing for some of my pain, for some of the struggles I have had.

That was most unexpected.

Because the story is written from the view of a 9 year old, there is a rawness of emotion expressed that is often glossed over by older people. There is an expectation of finding meaning that is far more hopeful than most adults have. There is a reality and a belief that the cynicism of age tends to dull. Most of all, there is an acceptance, at the end, that there is no meaning to be found. Oskar handles this because he has been on this journey, because he has spent time trying to find meaning. In the end, he is not distraught that there is no answer - he realises that he was asking the wrong question in the first place.

I think so often I ask the wrong questions. I then get frustrated when I cannot find answers. In Oskars search and revelation, there is a reminder that sometimes, I need to take the answer given, and search back for the question.

---

I am sorry that this posting has taken so long to get out. I have had an interesting and challenging few weeks, and have not been able to get any posts to a finished state. There are plenty more in a started state, plenty of ideas brewing, but finishing them has proved difficult. I hope I can do better in the weeks to come! Thank you.

Monday, 27 July 2015

Saturday, 11 July 2015

Ready Player One

I have recently finished reading this book, and it does raise some interesting questions. I will try to explore them without giving anything away about the story. There are three aspects that struck me:

1. When everything that we know is online, we need to know who owns the online. When we search the web, we use Google, who know and take the details of what we search for and when. When we communicate with others with email, we use Google, who track what we do, who we talk to, what we say.

When we use our phones, we might use an Android phone, again, written by Google. They can collect information from there about what we do on our phones, what applications we install.

Our web browser may well be Google too, if we use Chrome, and when we want to know where to go, we use Google maps. We trust Google with a lot of our information: Google owns the online.

Of course, we might refuse to go down the Google route, and have Microsoft or Apple as the organisation who own our online presence. But the truth is, one or other does, and we should know this, know that these companies own the online world.

Not to mention that if we buy anything online, there is a good chance that Amazon is involved. They do control a substantial portion of the online e-commerce world, by providing supply and distribution, or by owning the cloud computers that the software is running on.

However much we might not like it, we do have a lot of out information online, we all have a presence in the online world. We should know who owns it, and we should consider how much we trust them.

2. It is easy to forget the online world can impact the real world, the offline world. I for one do try to separate my online persona and my off-line one: not that I am different people between these environments, just that I try not to let on too much about who I am in real life online. Part of this is because information publicly available online is not safe.

But the reality is that someone who was determined could identify who I was in real life based on my online activity. This is true for all of us, however careful we are, not least because any information that is required to be made available to the public is available online, making it much easier to trace people. It is also the case, because a whole lot of information that is not public is accessible online, with a bit of work (not always legitimate).

So the truth is, if you don't like what I write in one of my blogs you could, if you were so inclined, find out who I am, where I live or work, and pay me a visit. I can hope that you post comments to me instead, engage in discussion. But I cannot dismiss the reality that the online writing and my real life could - and occasionally do - intersect.

3. Online community is real. I have been in so many discussions about whether online "church" is a real substitute for physical community. The truth is that it can be, although it need not be. I suspect a lot of the dismissal of "online community" comes from people who have been part of less welcoming and friendly communities.

But I have been a part of the Ship of Fools discussion boards for many years now. Aspects of this community are real and genuine, as much so as any other community. Occasionally, I will meet members of the community, which is always nice. I also meet other people, other Christians, who provide me with face-to-face interaction.

This last week, I have been on holiday, but someone I know has been extremely ill and requiring hospitalisation. I have kept up with events, and offered my prayer though technology. I have been as much part of that mini-community as I can, while being away, and that has been valuable. It is no less real, just because it is electronically mediated. Of course, practical help is harder, but I know there are people giving that.

Of course, there are dangers. There is always the danger that someone will present themselves online differently to how they actually are. I have experienced this, and it can be very damaging to a community. I have also experienced someone doing this in a real life group, and it is equally damaging. It is not purely an online problem. There is a danger that people will substitute virtual interaction for "real life" interaction - in the same way that people can spend all of their time at church and in church activities, and avoid anything and anyone else.

The book overall does have weaknesses. It may be a little simplistic. It may be a little more Willy Wonka than The Matrix. But it is a good read, and it does make you think. Well, it made me thing, at least.

1. When everything that we know is online, we need to know who owns the online. When we search the web, we use Google, who know and take the details of what we search for and when. When we communicate with others with email, we use Google, who track what we do, who we talk to, what we say.

When we use our phones, we might use an Android phone, again, written by Google. They can collect information from there about what we do on our phones, what applications we install.

Our web browser may well be Google too, if we use Chrome, and when we want to know where to go, we use Google maps. We trust Google with a lot of our information: Google owns the online.

Of course, we might refuse to go down the Google route, and have Microsoft or Apple as the organisation who own our online presence. But the truth is, one or other does, and we should know this, know that these companies own the online world.

Not to mention that if we buy anything online, there is a good chance that Amazon is involved. They do control a substantial portion of the online e-commerce world, by providing supply and distribution, or by owning the cloud computers that the software is running on.

However much we might not like it, we do have a lot of out information online, we all have a presence in the online world. We should know who owns it, and we should consider how much we trust them.

2. It is easy to forget the online world can impact the real world, the offline world. I for one do try to separate my online persona and my off-line one: not that I am different people between these environments, just that I try not to let on too much about who I am in real life online. Part of this is because information publicly available online is not safe.

But the reality is that someone who was determined could identify who I was in real life based on my online activity. This is true for all of us, however careful we are, not least because any information that is required to be made available to the public is available online, making it much easier to trace people. It is also the case, because a whole lot of information that is not public is accessible online, with a bit of work (not always legitimate).

So the truth is, if you don't like what I write in one of my blogs you could, if you were so inclined, find out who I am, where I live or work, and pay me a visit. I can hope that you post comments to me instead, engage in discussion. But I cannot dismiss the reality that the online writing and my real life could - and occasionally do - intersect.

3. Online community is real. I have been in so many discussions about whether online "church" is a real substitute for physical community. The truth is that it can be, although it need not be. I suspect a lot of the dismissal of "online community" comes from people who have been part of less welcoming and friendly communities.

But I have been a part of the Ship of Fools discussion boards for many years now. Aspects of this community are real and genuine, as much so as any other community. Occasionally, I will meet members of the community, which is always nice. I also meet other people, other Christians, who provide me with face-to-face interaction.

This last week, I have been on holiday, but someone I know has been extremely ill and requiring hospitalisation. I have kept up with events, and offered my prayer though technology. I have been as much part of that mini-community as I can, while being away, and that has been valuable. It is no less real, just because it is electronically mediated. Of course, practical help is harder, but I know there are people giving that.

Of course, there are dangers. There is always the danger that someone will present themselves online differently to how they actually are. I have experienced this, and it can be very damaging to a community. I have also experienced someone doing this in a real life group, and it is equally damaging. It is not purely an online problem. There is a danger that people will substitute virtual interaction for "real life" interaction - in the same way that people can spend all of their time at church and in church activities, and avoid anything and anyone else.

The book overall does have weaknesses. It may be a little simplistic. It may be a little more Willy Wonka than The Matrix. But it is a good read, and it does make you think. Well, it made me thing, at least.

Thursday, 2 July 2015

I am not a "Done"

In a recent report, people like me who have left the church were referred to as "Dones". I took exception to this - Robb Sutherland pointed out that this was not the worst of the churches terminology, which is true, but it applies to ME, which makes it personal.

I do realise that this is partly to make it like the other category they talked about "Nones" (those whose answer to a religion question put "None"). I know how churches like to have lists of items that rhyme (or alliterate, or form an acrostic), and how no doctrine can be acceptable if it cannot be expressed in such terms, but that is no excuse for labelling me with a term that I find uncomfortable.

The reason I have a problem with the term is that is defined as people who have said they are "done" with church. It sounds like an individualistic expression that I have got over my "church" phase, that I have moved on from this. There are people who have done that, moved on, decided that they have "done" with church. But that is not me, and that is not many of those who I have spoken to who have left the church.

At heart, I think the reason is that I feel the church has rejected me, rather than the other way round. The church has not been able to encapsulate my expression of faith. And yet, if that is valid Christianity (and I believe it is), what is more, if it is valid evangelical Christianity (and I believe it is), then it is the church which seems to have decided that I am not a key expression of this style of faith.

So I am not a "done". I would accept that I have, for now, stopped attending church, as it is not helpful in this stage of my life. But it is not a selfish, huff, stumping off because the church doesn't do what I want. It is a conscious, careful decision that the church was not a positive influence in my faith journey. They had rejected the route I was taking.

Why is this important? Because it is about where changes happen. If it is my fault, me storming off, then I need to change, to re-confirm to the church's expectation. That seems to be the implication off being a "done". Whereas if it is the church that has rejected me - and many others: lets be clear this is not just personal - then it is the church that may need to change, to find a way of accepting me.

In truth, there is probably a bit of both. But I believe that the church does need to make the largest move. If it has any real concern about me and people like me - who have been core members of the church, but find that the church does not move - it needs to be radically different, radically changed. I didn't leave because of some small, minor disagreement. I left because I believe that the church is no longer the place to support my faith and my engagement with others.

This is not just about me. the church is haemorrhaging good, involved, top people. So often the answer is to draw more people into the church, whereas the real solution is for the church to move and find ways of accepting people on the edges, to be making the edges the centre.

I do realise that this is partly to make it like the other category they talked about "Nones" (those whose answer to a religion question put "None"). I know how churches like to have lists of items that rhyme (or alliterate, or form an acrostic), and how no doctrine can be acceptable if it cannot be expressed in such terms, but that is no excuse for labelling me with a term that I find uncomfortable.

The reason I have a problem with the term is that is defined as people who have said they are "done" with church. It sounds like an individualistic expression that I have got over my "church" phase, that I have moved on from this. There are people who have done that, moved on, decided that they have "done" with church. But that is not me, and that is not many of those who I have spoken to who have left the church.

At heart, I think the reason is that I feel the church has rejected me, rather than the other way round. The church has not been able to encapsulate my expression of faith. And yet, if that is valid Christianity (and I believe it is), what is more, if it is valid evangelical Christianity (and I believe it is), then it is the church which seems to have decided that I am not a key expression of this style of faith.

So I am not a "done". I would accept that I have, for now, stopped attending church, as it is not helpful in this stage of my life. But it is not a selfish, huff, stumping off because the church doesn't do what I want. It is a conscious, careful decision that the church was not a positive influence in my faith journey. They had rejected the route I was taking.

Why is this important? Because it is about where changes happen. If it is my fault, me storming off, then I need to change, to re-confirm to the church's expectation. That seems to be the implication off being a "done". Whereas if it is the church that has rejected me - and many others: lets be clear this is not just personal - then it is the church that may need to change, to find a way of accepting me.

In truth, there is probably a bit of both. But I believe that the church does need to make the largest move. If it has any real concern about me and people like me - who have been core members of the church, but find that the church does not move - it needs to be radically different, radically changed. I didn't leave because of some small, minor disagreement. I left because I believe that the church is no longer the place to support my faith and my engagement with others.

This is not just about me. the church is haemorrhaging good, involved, top people. So often the answer is to draw more people into the church, whereas the real solution is for the church to move and find ways of accepting people on the edges, to be making the edges the centre.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)